The Kukulkan Pyramid in Chichen-Itza which known as “El Castillo” (the castle)

Chichen Itza is one of Mexico’s most popular tourist destination, and rightfully so. The Yucatan’s grandest archaeological site is Chichen-Itza, a UNESCO World Heritage area of immense cultural significance.

Chichen Itza is perhaps the largest, most famous and most accessible Mayan site, about 125 kilometres west of Cancun and Cozumel. This ancient Mayan ruin, a major tourist stop in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, is a rugged place of soaring pyramids, massive temples, startling carved columns and do-or-die sports fields.

The focal point of the region, an amalgam of an older Mayan city and newer Toltec settlement, is the towering Castillo pyramid, which is fraught with cosmological symbolism. Its four sides contain 365 steps (depicting the solar year), 52 panels (for each year in the Mayan century as well as each week in the solar year) and 18 terraces (for the 18 months in the religious year). Inside, the Castillo is an interesting temple accessible up a narrow stairway.

Mayan sports included a game with a soccer-sized ball that had its own intricate rules and provided exciting competition for huge crowds of spectators.

The enormous Chichen-Itza court where this game was played is the largest ever found and is lined with fascinating carvings that display the rules and details of the sacred game.

One carving even shows the captain of the losing game being beheaded.

The site also contains a sacred well, the astronomical Observatory, the imposing Temple of Warriors, the reclining Chac Mool figure, a form of classic Maya sculpture believed to have served as an altar for sacrifices, and the Nunnery.

During the fall and spring equinoxes, the sun’s shadow forms an enormous snake’s body, which lines up with the carved stone snake head at the bottom of the Castillo pyramid.

At Chichen Itza, the Sacred Cenote is a natural well 60 metres in diameter with sheer, escape-proof walls plunging 22 metres. Winsome maidens aside, excavations in 1882 and 1968 discovered that strapping six-foot warriors – old scores settled? – and infants were also tossed into the pit.

Across from El Castillo, the Temple of the Warriors is also known as the Temple of the Thousand Columns. On top of it there is a stone on which steaming human hearts were offered to the gods.

Paintings on the outdoor pillars have all but disappeared, but inside an older temple beneath this one, colors are as bright as when they were freshly mixed from vegetable juice and mashed insects.

Several smaller buildings hold interest mostly for their relief sculptures depicting dire events of the time. But one that really makes you sit up and pay attention is a huge ball park.

Each of two 27-foot-high walls running its 480-foot length has a small stone ring near the top, through which a hard rubber ball had to be shot.

When you cross the highway bisecting the archeological zone, you leave behind unpleasant murals and evidence of human sacrifice, for these are buildings from pre-Toltec times. Unfortunately the Spaniards destroyed all religious records.

In consequence, nobody knows for certain that the ornate structure, 70 yards long and 18 yards high, was actually a nunnery.

However, built in 600 A.d. beside a church, it has many little rooms reminiscent of the convents in Spain so they named it the Nunnery.

In Chichen Itza you can also find the Caracol (Spanish for snail), so called for its spiral staircase. The substructure is believed to have been completed around 700 A.D., and the 48-foot circular tower added later. This is the all-important observatory.

El Castillo

El Castillo (Spanish pronunciation: [el kas’tiʎo]), Spanish for “the castle”), also known as the Temple of Kukulcan, is a Mesoamerican step-pyramid that dominates the center of the Chichen Itza archaeological site in the Mexican state of Yucatán. The building is more formally designated by archaeologists as Chichen Itza Structure 5B18.

Built by the pre-Columbian Maya civilization sometime between the 9th and 12th centuries CE, El Castillo served as a temple to the god Kukulkan, the Yucatec Maya Feathered Serpent deity closely related to the god Quetzalcoatl known to the Aztecs and other central Mexican cultures of the Postclassic period.

The pyramid consists of a series of square terraces with stairways up each of the four sides to the temple on top. Sculptures of plumed serpents run down the sides of the northern balustrade. During the spring and autumn equinoxes, the late afternoon sun strikes off the northwest corner of the pyramid and casts a series of triangular shadows against the northwest balustrade, creating the illusion of a feathered serpent “crawling” down the pyramid. The event has been very popular, but it is questionable whether it is a result of a purposeful design. Each of the pyramid’s four sides has 91 steps which, when added together and including the temple platform on top as the final “step”, produces a total of 365 steps (which is equal to the number of days of the Haab’ year).

The structure is 24 m (79 ft) high, plus an additional 6 m (20 ft) for the temple. The square base measures 55.3 m (181 ft) across.

History

The history of Chichen Itza can be traced back to the classic period of Mayan civilization , running between 250 BC through AD 850. Geographically, it ranged from Mexico through Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and El Salvador.

During the first millennium AD, the Mayans reached levels of civilization rivalling those of ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome.

They were superb astronomers, architect/builders, athletes and mathematicians.

But for some unfathomable reason they never discovered the wheel.

In times when Chichen Itza flourished as a city, the Mayas formed a highly sophisticated society. Their elite did remarkable work in astronomy, mathematics, engineering and architecture, while the rest provided manpower to execute the plans.

Largest of Mayan cities, Chichen Itza was started around 400 A.D., abandoned and returned to several times before the Toltecs arrived in 987 A.D.

The aggressive Toltecs conquered the Itzas, introduced them to the practice of human sacrifice and with their labor rebuilt the city as a religious centre.

Everyone moved out by the thirteenth century, so when the Spaniards came in the 1500s they found crumbling buildings being devoured by the greedy jungle.

A New York lawyer rediscovered them in 1842, following which an influx of amateur archeologists destroyed some.

Real restoration and reconstruction by the Carnegie Institute and Mexican government was begun in 1922, and continued for 20 years.

Site description

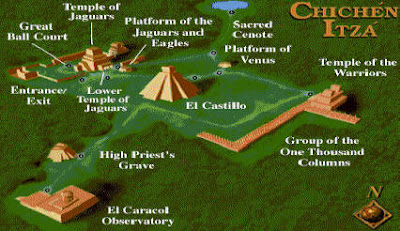

Chichen Itza was one of the largest Maya cities, with the relatively densely clustered architecture of the site core covering an area of at least 5 square kilometres (1.9 sq mi). Smaller scale residential architecture extends for an unknown distance beyond this. The city was built upon broken terrain, which was artificially levelled in order to build the major architectural groups, with the greatest effort being expended in the levelling of the areas for the Castillo pyramid, and the Las Monjas, Osario and Main Southwest groups.

The site contains many fine stone buildings in various states of preservation, and many have been restored. The buildings were connected by a dense network of paved causeways, called sacbeob. Archaeologists have identified over 80 sacbeob criss-crossing the site, and extending in all directions from the city.

The architecture encompasses a number of styles, including the Puuc and Chenes styles of the northern Yucatán Peninsula. The buildings of Chichen Itza are grouped in a series of architectonic sets, and each set was at one time separated from the other by a series of low walls. The three best known of these complexes are the Great North Platform, which includes the monuments of El Castillo, Temple of Warriors and the Great Ball Court; The Osario Group, which includes the pyramid of the same name as well as the Temple of Xtoloc; and the Central Group, which includes the Caracol, Las Monjas, and Akab Dzib.

South of Las Monjas, in an area known as Chichén Viejo (Old Chichén) and only open to archaeologists, are several other complexes, such as the Group of the Initial Series, Group of the Lintels, and Group of the Old Castle.

Architectural styles

The Puuc-style architecture is concentrated in the Old Chichen area, and also the earlier structures in the Nunnery Group (including the Las Monjas, Annex and La Iglesia buildings); it is also represented in the Akab Dzib structure. The Puuc-style building feature the usual mosaic-decorated upper façades characteristic of the style but differ from the architecture of the Puuc heartland in their block masonry walls, as opposed to the fine veneers of the Puuc region proper.

At least one structure in the Las Monjas Group features an ornate façade and masked doorway that are typical examples of Chenes-style architecture, a style centred upon a region in the north of Campeche state, lying between the Puuc and Río Bec regions.

Those structures with sculpted hieroglyphic script are concentrated in certain areas of the site, with the most important being the Las Monjas group.

Architectural groups

Great North Platform

Dominating the North Platform of Chichen Itza is the Temple of Kukulkan (a Maya feathered serpent deity similar to the Aztec Quetzalcoatl), usually referred to as El Castillo ("the castle"). This step pyramid stands about 30 metres (98 ft) high and consists of a series of nine square terraces, each approximately 2.57 metres (8.4 ft) high, with a 6-metre (20 ft) high temple upon the summit.

The sides of the pyramid are approximately 55.3 metres (181 ft) at the base and rise at an angle of 53°, although that varies slightly for each side. The four faces of the pyramid have protruding stairways that rise at an angle of 45°.The talud walls of each terrace slant at an angle of between 72° and 74°.At the base of the balustrades of the northeastern staircase are carved heads of a serpent.

Mesoamerican cultures periodically superimposed larger structures over older ones,and El Castillo is one such example. In the mid-1930s, the Mexican government sponsored an excavation of El Castillo. After several false starts, they discovered a staircase under the north side of the pyramid. By digging from the top, they found another temple buried below the current one.

Inside the temple chamber was a Chac Mool statue and a throne in the shape of Jaguar, painted red and with spots made of inlaid jade. The Mexican government excavated a tunnel from the base of the north staircase, up the earlier pyramid’s stairway to the hidden temple, and opened it to tourists. In 2006, INAH closed the throne room to the public.

On the Spring and Autumn equinoxes, in the late afternoon, the northwest corner of the pyramid casts a series of triangular shadows against the western balustrade on the north side that evokes the appearance of a serpent wriggling down the staircase, which some scholars have suggested is a representation of the feathered-serpent god Kukulkan.

Archaeologists have identified thirteen ballcourts for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame in Chichen Itza, but the Great Ball Court about 150 metres (490 ft) to the north-west of the Castillo is by far the most impressive. It is the largest and best preserved ball court in ancient Mesoamerica. It measures 168 by 70 metres (551 by 230 ft).

The parallel platforms flanking the main playing area are each 95 metres (312 ft) long. The walls of these platforms stand 8 metres (26 ft) high;set high up in the centre of each of these walls are rings carved with intertwined feathered serpents.

At the base of the high interior walls are slanted benches with sculpted panels of teams of ball players. In one panel, one of the players has been decapitated; the wound emits streams of blood in the form of wriggling snakes.

At one end of the Great Ball Court is the North Temple, also known as the Temple of the Bearded Man (Templo del Hombre Barbado). This small masonry building has detailed bas relief carving on the inner walls, including a center figure that has carving under his chin that resembles facial hair. At the south end is another, much bigger temple, but in ruins.

Built into the east wall are the Temples of the Jaguar. The Upper Temple of the Jaguar overlooks the ball court and has an entrance guarded by two, large columns carved in the familiar feathered serpent motif. Inside there is a large mural, much destroyed, which depicts a battle scene.

In the entrance to the Lower Temple of the Jaguar, which opens behind the ball court, is another Jaguar throne, similar to the one in the inner temple of El Castillo, except that it is well worn and missing paint or other decoration. The outer columns and the walls inside the temple are covered with elaborate bas-relief carvings.

Additional structures

The Tzompantli, or Skull Platform (Plataforma de los Cráneos), shows the clear cultural influence of the central Mexican Plateau. Unlike the tzompantli of the highlands, however, the skulls were impaled vertically rather than horizontally as at Tenochtitlan.

The Platform of the Eagles and the Jaguars (Plataforma de Águilas y Jaguares) is immediately to the east of the Great Ballcourt. It is built in a combination Maya and Toltec styles, with a staircase ascending each of its four sides. The sides are decorated with panels depicting eagles and jaguars consuming human hearts.

This Platform of Venus is dedicated to the planet Venus. In its interior archaeologists discovered a collection of large cones carved out of stone,the purpose of which is unknown. This platform is located north of El Castillo, between it and the Cenote Sagrado.

The Temple of the Tables is the northernmost of a series of buildings to the east of El Castillo. Its name comes from a series of altars at the top of the structure that are supported by small carved figures of men with upraised arms, called “atlantes.”

The Steam Bath is a unique building with three parts: a waiting gallery, a water bath, and a steam chamber that operated by means of heated stones.

Sacbe Number One is a causeway that leads to the Cenote Sagrado, is the largest and most elaborate at Chichen Itza. This “white road” is 270 metres (890 ft) long with an average width of 9 metres (30 ft). It begins at a low wall a few metres from the Platform of Venus. According to archaeologists there once was an extensive building with columns at the beginning of the road.

The Yucatán Peninsula is a limestone plain, with no rivers or streams. The region is pockmarked with natural sinkholes, called cenotes, which expose the water table to the surface. One of the most impressive of these is the Cenote Sagrado, which is 60 metres (200 ft) in diameter and surrounded by sheer cliffs that drop to the water table some 27 metres (89 ft) below.

The Cenote Sagrado was a place of pilgrimage for ancient Maya people who, according to ethnohistoric sources, would conduct sacrifices during times of drought. Archaeological investigations support this as thousands of objects have been removed from the bottom of the cenote, including material such as gold, carved jade, copal, pottery, flint, obsidian, shell, wood, rubber, cloth, as well as skeletons of children and men.

The Temple of the Warriors complex consists of a large stepped pyramid fronted and flanked by rows of carved columns depicting warriors. This complex is analogous to Temple B at the Toltec capital of Tula, and indicates some form of cultural contact between the two regions. The one at Chichen Itza, however, was constructed on a larger scale. At the top of the stairway on the pyramid’s summit (and leading towards the entrance of the pyramid’s temple) is a Chac Mool.

This temple encases or entombs a former structure called The Temple of the Chac Mool. The archeological expedition and restoration of this building was done by the Carnegie Institution of Washington from 1925 to 1928. A key member of this restoration was Earl H. Morris who published the work from this expedition in two volumes entitled Temple of the Warriors.

Along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors are a series of what are today exposed columns, although when the city was inhabited these would have supported an extensive roof system. The columns are in three distinct sections: A west group, that extends the lines of the front of the Temple of Warriors. A north group runs along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors and contains pillars with carvings of soldiers in bas-relief;

A northeast group, which apparently formed a small temple at the southeast corner of the Temple of Warriors, contains a rectangular decorated with carvings of people or gods, as well as animals and serpents. The northeast column temple also covers a small marvel of engineering, a channel that funnels all the rainwater from the complex some 40 metres (130 ft) away to a rejollada, a former cenote.

To the south of the Group of a Thousand Columns is a group of three, smaller, interconnected buildings. The Temple of the Carved Columns is a small elegant building that consists of a front gallery with an inner corridor that leads to an altar with a Chac Mool. There are also numerous columns with rich, bas-relief carvings of some 40 personages.

A section of the upper façade with a motif of x’s and o’s is displayed in front of the structure. The Temple of the Small Tables which is an unrestored mound. And the Thompson’s Temple (referred to in some sources as Palace of Ahau Balam Kauil ), a small building with two levels that has friezes depicting Jaguars (balam in Maya) as well as glyphs of the Maya god Kahuil.

This square structure anchors the southern end of the Temple of Warriors complex. It is so named for the shelf of stone that surrounds a large gallery and patio that early explorers theorized was used to display wares as in a marketplace. Today, archaeologists believe that its purpose was more ceremonial than commercial.

South of the North Group is a smaller platform that has many important structures, several of which appear to be oriented toward the second largest cenote at Chichen Itza, Xtoloc.

The Osario itself, like El Castillo, is a step-pyramid temple dominating its platform, only on a smaller scale. Like its larger neighbor, it has four sides with staircases on each side. There is a temple on top, but unlike El Castillo, at the center is an opening into the pyramid which leads to a natural cave 12 metres (39 ft) below. Edward H. Thompson excavated this cave in the late 19th century, and because he found several skeletons and artifacts such as jade beads, he named the structure The High Priests' Temple. Archaeologists today believe the structure was neither a tomb nor that the personages buried in it were priests.

The Temple of Xtoloc is a recently restored temple outside the Osario Platform is. It overlooks the other large cenote at Chichen Itza, named after the Maya word for iguana, "Xtoloc." The temple contains a series of pilasters carved with images of people, as well as representations of plants, birds and mythological scenes.

Between the Xtoloc temple and the Osario are several aligned structures: The Platform of Venus (which is similar in design to the structure of the same name next to El Castillo), the Platform of the Tombs, and a small, round structure that is unnamed. These three structures were constructed in a row extending from the Osario. Beyond them the Osario platform terminates in a wall, which contains an opening to a sacbe that runs several hundred feet to the Xtoloc temple.

South of the Osario, at the boundary of the platform, there are two small buildings that archaeologists believe were residences for important personages. These have been named as the House of the Metates and the House of the Mestizas.

South of the Osario Group is another small platform that has several structures that are among the oldest in the Chichen Itza archaeological zone.

The Casa Colorada (Spanish for "Red House") is one of the best preserved buildings at Chichen Itza. Its Maya name is Chichanchob, which according to INAH may mean "small holes". In one chamber there are extensive carved hieroglyphs that mention rulers of Chichen Itza and possibly of the nearby city of Ek Balam, and contain a Maya date inscribed which correlates to 869 AD, one of the oldest such dates found in all of Chichen Itza.

In 2009, INAH restored a small ball court that adjoined the back wall of the Casa Colorada.

While the Casa Colorada is in a good state of preservation, other buildings in the group, with one exception, are decrepit mounds. One building is half standing, named Casa del Venado (House of the Deer). The origin of the name is unknown, as there are no representations of deer or other animals on the building.

"La Iglesia" in the Las Monjas complex.

The "El Caracol" observatory temple.

Las Monjas is one of the more notable structures at Chichen Itza. It is a complex of Terminal Classic buildings constructed in the Puuc architectural style. The Spanish named this complex Las Monjas ("The Nuns" or "The Nunnery") but it was actually a governmental palace. Just to the east is a small temple (known as the La Iglesia, "The Church") decorated with elaborate masks.

The Las Monjas group is distinguished by its concentration of hieroglyphic texts dating to the Late to Terminal Classic. These texts frequently mention a ruler by the name of Kakupakal.

El Caracol ("The Snail") is located to the north of Las Monjas. It is a round building on a large square platform. It gets its name from the stone spiral staircase inside. The structure, with its unusual placement on the platform and its round shape (the others are rectangular, in keeping with Maya practice), is theorized to have been a proto-observatory with doors and windows aligned to astronomical events, specifically around the path of Venus as it traverses the heavens.

Akab Dzib is located to the east of the Caracol. The name means, in Yucatec Mayan, "Dark Writing"; "dark" in the sense of "mysterious". An earlier name of the building, according to a translation of glyphs in the Casa Colorada, is Wa(k)wak Puh Ak Na, "the flat house with the excessive number of chambers,” and it was the home of the administrator of Chichén Itzá, kokom Yahawal Cho' K’ak’.

INAH completed a restoration of the building in 2007. It is relatively short, only 6 metres (20 ft) high, and is 50 metres (160 ft) in length and 15 metres (49 ft) wide. The long, western-facing façade has seven doorways. The eastern façade has only four doorways, broken by a large staircase that leads to the roof. This apparently was the front of the structure, and looks out over what is today a steep, dry, cenote.

The southern end of the building has one entrance. The door opens into a small chamber and on the opposite wall is another doorway, above which on the lintel are intricately carved glyphs—the “mysterious” or “obscure” writing that gives the building its name today. Under the lintel in the doorjamb is another carved panel of a seated figure surrounded by more glyphs. Inside one of the chambers, near the ceiling, is a painted hand print.

Composite laser scan image of Chichen Itza's Cave of Balankanche, showing how the shape of its great limestone column is strongly evocative of the World Tree in Maya mythological belief systems. Data from a National Science Foundation/CyArk research partnership.

Old Chichen (or Chichén Viejo in Spanish) is the name given to a group of structures to the south of the central site, where most of the Puuc-style architecture of the city is concentrated.[4] It includes the Initial Series Group, the Phallic Temple, the Platform of the Great Turtle, the Temple of the Owls, and the Temple of the Monkeys.

Chichen Itza also has a variety of other structures densely packed in the ceremonial center of about 5 square kilometres (1.9 sq mi) and several outlying subsidiary sites.

Caves of Balankanche

Approximately 4 km (2.5 mi) south east of the Chichen Itza archaeological zone are a network of sacred caves known as Balankanche (Spanish: Gruta de Balankanche), Balamka'anche' in Yucatec Maya). In the caves, a large selection of ancient pottery and idols may be seen still in the positions where they were left in pre-Columbian times.

The location of the cave has been well known in modern times. Edward Thompson and Alfred Tozzer visited it in 1905. A.S. Pearse and a team of biologists explored the cave in 1932 and 1936. E. Wyllys Andrews IV also explored the cave in the 1930s. Edwin Shook and R.E. Smith explored the cave on behalf of the Carnegie Institution in 1954, and dug several trenches to recover potsherds and other artifacts. Shook determined that the cave had been inhabited over a long period, at least from the Preclassic to the post-conquest era.

On 15 September 1959, José Humberto Gómez, a local guide, discovered a false wall in the cave. Behind it he found an extended network of caves with significant quantities of undisturbed archaeological remains, including pottery and stone-carved censers, stone implements and jewelry. INAH converted the cave into an underground museum, and the objects after being catalogued were returned to their original place so visitors can see them in situ.

Chichen Itza was one of the largest Maya cities, with the relatively densely clustered architecture of the site core covering an area of at least 5 square kilometres (1.9 sq mi). Smaller scale residential architecture extends for an unknown distance beyond this. The city was built upon broken terrain, which was artificially levelled in order to build the major architectural groups, with the greatest effort being expended in the levelling of the areas for the Castillo pyramid, and the Las Monjas, Osario and Main Southwest groups.

The site contains many fine stone buildings in various states of preservation, and many have been restored. The buildings were connected by a dense network of paved causeways, called sacbeob. Archaeologists have identified over 80 sacbeob criss-crossing the site, and extending in all directions from the city.

The architecture encompasses a number of styles, including the Puuc and Chenes styles of the northern Yucatán Peninsula. The buildings of Chichen Itza are grouped in a series of architectonic sets, and each set was at one time separated from the other by a series of low walls. The three best known of these complexes are the Great North Platform, which includes the monuments of El Castillo, Temple of Warriors and the Great Ball Court; The Osario Group, which includes the pyramid of the same name as well as the Temple of Xtoloc; and the Central Group, which includes the Caracol, Las Monjas, and Akab Dzib.

South of Las Monjas, in an area known as Chichén Viejo (Old Chichén) and only open to archaeologists, are several other complexes, such as the Group of the Initial Series, Group of the Lintels, and Group of the Old Castle.

Architectural styles

The Puuc-style architecture is concentrated in the Old Chichen area, and also the earlier structures in the Nunnery Group (including the Las Monjas, Annex and La Iglesia buildings); it is also represented in the Akab Dzib structure. The Puuc-style building feature the usual mosaic-decorated upper façades characteristic of the style but differ from the architecture of the Puuc heartland in their block masonry walls, as opposed to the fine veneers of the Puuc region proper.

At least one structure in the Las Monjas Group features an ornate façade and masked doorway that are typical examples of Chenes-style architecture, a style centred upon a region in the north of Campeche state, lying between the Puuc and Río Bec regions.

Those structures with sculpted hieroglyphic script are concentrated in certain areas of the site, with the most important being the Las Monjas group.

Architectural groups

Great North Platform

El Castillo

Dominating the North Platform of Chichen Itza is the Temple of Kukulkan (a Maya feathered serpent deity similar to the Aztec Quetzalcoatl), usually referred to as El Castillo ("the castle"). This step pyramid stands about 30 metres (98 ft) high and consists of a series of nine square terraces, each approximately 2.57 metres (8.4 ft) high, with a 6-metre (20 ft) high temple upon the summit.

The sides of the pyramid are approximately 55.3 metres (181 ft) at the base and rise at an angle of 53°, although that varies slightly for each side. The four faces of the pyramid have protruding stairways that rise at an angle of 45°.The talud walls of each terrace slant at an angle of between 72° and 74°.At the base of the balustrades of the northeastern staircase are carved heads of a serpent.

Mesoamerican cultures periodically superimposed larger structures over older ones,and El Castillo is one such example. In the mid-1930s, the Mexican government sponsored an excavation of El Castillo. After several false starts, they discovered a staircase under the north side of the pyramid. By digging from the top, they found another temple buried below the current one.

Inside the temple chamber was a Chac Mool statue and a throne in the shape of Jaguar, painted red and with spots made of inlaid jade. The Mexican government excavated a tunnel from the base of the north staircase, up the earlier pyramid’s stairway to the hidden temple, and opened it to tourists. In 2006, INAH closed the throne room to the public.

On the Spring and Autumn equinoxes, in the late afternoon, the northwest corner of the pyramid casts a series of triangular shadows against the western balustrade on the north side that evokes the appearance of a serpent wriggling down the staircase, which some scholars have suggested is a representation of the feathered-serpent god Kukulkan.

Great Ball Court

Archaeologists have identified thirteen ballcourts for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame in Chichen Itza, but the Great Ball Court about 150 metres (490 ft) to the north-west of the Castillo is by far the most impressive. It is the largest and best preserved ball court in ancient Mesoamerica. It measures 168 by 70 metres (551 by 230 ft).

The parallel platforms flanking the main playing area are each 95 metres (312 ft) long. The walls of these platforms stand 8 metres (26 ft) high;set high up in the centre of each of these walls are rings carved with intertwined feathered serpents.

At the base of the high interior walls are slanted benches with sculpted panels of teams of ball players. In one panel, one of the players has been decapitated; the wound emits streams of blood in the form of wriggling snakes.

At one end of the Great Ball Court is the North Temple, also known as the Temple of the Bearded Man (Templo del Hombre Barbado). This small masonry building has detailed bas relief carving on the inner walls, including a center figure that has carving under his chin that resembles facial hair. At the south end is another, much bigger temple, but in ruins.

Built into the east wall are the Temples of the Jaguar. The Upper Temple of the Jaguar overlooks the ball court and has an entrance guarded by two, large columns carved in the familiar feathered serpent motif. Inside there is a large mural, much destroyed, which depicts a battle scene.

In the entrance to the Lower Temple of the Jaguar, which opens behind the ball court, is another Jaguar throne, similar to the one in the inner temple of El Castillo, except that it is well worn and missing paint or other decoration. The outer columns and the walls inside the temple are covered with elaborate bas-relief carvings.

Additional structures

The Tzompantli, or Skull Platform (Plataforma de los Cráneos), shows the clear cultural influence of the central Mexican Plateau. Unlike the tzompantli of the highlands, however, the skulls were impaled vertically rather than horizontally as at Tenochtitlan.

The Platform of the Eagles and the Jaguars (Plataforma de Águilas y Jaguares) is immediately to the east of the Great Ballcourt. It is built in a combination Maya and Toltec styles, with a staircase ascending each of its four sides. The sides are decorated with panels depicting eagles and jaguars consuming human hearts.

This Platform of Venus is dedicated to the planet Venus. In its interior archaeologists discovered a collection of large cones carved out of stone,the purpose of which is unknown. This platform is located north of El Castillo, between it and the Cenote Sagrado.

The Temple of the Tables is the northernmost of a series of buildings to the east of El Castillo. Its name comes from a series of altars at the top of the structure that are supported by small carved figures of men with upraised arms, called “atlantes.”

The Steam Bath is a unique building with three parts: a waiting gallery, a water bath, and a steam chamber that operated by means of heated stones.

Sacbe Number One is a causeway that leads to the Cenote Sagrado, is the largest and most elaborate at Chichen Itza. This “white road” is 270 metres (890 ft) long with an average width of 9 metres (30 ft). It begins at a low wall a few metres from the Platform of Venus. According to archaeologists there once was an extensive building with columns at the beginning of the road.

Sacred Cenote

The Yucatán Peninsula is a limestone plain, with no rivers or streams. The region is pockmarked with natural sinkholes, called cenotes, which expose the water table to the surface. One of the most impressive of these is the Cenote Sagrado, which is 60 metres (200 ft) in diameter and surrounded by sheer cliffs that drop to the water table some 27 metres (89 ft) below.

The Cenote Sagrado was a place of pilgrimage for ancient Maya people who, according to ethnohistoric sources, would conduct sacrifices during times of drought. Archaeological investigations support this as thousands of objects have been removed from the bottom of the cenote, including material such as gold, carved jade, copal, pottery, flint, obsidian, shell, wood, rubber, cloth, as well as skeletons of children and men.

Templo de los Guerreros (Temple of the Warriors)

The Temple of the Warriors complex consists of a large stepped pyramid fronted and flanked by rows of carved columns depicting warriors. This complex is analogous to Temple B at the Toltec capital of Tula, and indicates some form of cultural contact between the two regions. The one at Chichen Itza, however, was constructed on a larger scale. At the top of the stairway on the pyramid’s summit (and leading towards the entrance of the pyramid’s temple) is a Chac Mool.

This temple encases or entombs a former structure called The Temple of the Chac Mool. The archeological expedition and restoration of this building was done by the Carnegie Institution of Washington from 1925 to 1928. A key member of this restoration was Earl H. Morris who published the work from this expedition in two volumes entitled Temple of the Warriors.

Group of a Thousand Columns

A northeast group, which apparently formed a small temple at the southeast corner of the Temple of Warriors, contains a rectangular decorated with carvings of people or gods, as well as animals and serpents. The northeast column temple also covers a small marvel of engineering, a channel that funnels all the rainwater from the complex some 40 metres (130 ft) away to a rejollada, a former cenote.

To the south of the Group of a Thousand Columns is a group of three, smaller, interconnected buildings. The Temple of the Carved Columns is a small elegant building that consists of a front gallery with an inner corridor that leads to an altar with a Chac Mool. There are also numerous columns with rich, bas-relief carvings of some 40 personages.

A section of the upper façade with a motif of x’s and o’s is displayed in front of the structure. The Temple of the Small Tables which is an unrestored mound. And the Thompson’s Temple (referred to in some sources as Palace of Ahau Balam Kauil ), a small building with two levels that has friezes depicting Jaguars (balam in Maya) as well as glyphs of the Maya god Kahuil.

El Mercado

Osario Group

The Osario itself, like El Castillo, is a step-pyramid temple dominating its platform, only on a smaller scale. Like its larger neighbor, it has four sides with staircases on each side. There is a temple on top, but unlike El Castillo, at the center is an opening into the pyramid which leads to a natural cave 12 metres (39 ft) below. Edward H. Thompson excavated this cave in the late 19th century, and because he found several skeletons and artifacts such as jade beads, he named the structure The High Priests' Temple. Archaeologists today believe the structure was neither a tomb nor that the personages buried in it were priests.

Temple of Xtoloc

The Temple of Xtoloc is a recently restored temple outside the Osario Platform is. It overlooks the other large cenote at Chichen Itza, named after the Maya word for iguana, "Xtoloc." The temple contains a series of pilasters carved with images of people, as well as representations of plants, birds and mythological scenes.

Between the Xtoloc temple and the Osario are several aligned structures: The Platform of Venus (which is similar in design to the structure of the same name next to El Castillo), the Platform of the Tombs, and a small, round structure that is unnamed. These three structures were constructed in a row extending from the Osario. Beyond them the Osario platform terminates in a wall, which contains an opening to a sacbe that runs several hundred feet to the Xtoloc temple.

South of the Osario, at the boundary of the platform, there are two small buildings that archaeologists believe were residences for important personages. These have been named as the House of the Metates and the House of the Mestizas.

Casa Colorada Group

The Casa Colorada (Spanish for "Red House") is one of the best preserved buildings at Chichen Itza. Its Maya name is Chichanchob, which according to INAH may mean "small holes". In one chamber there are extensive carved hieroglyphs that mention rulers of Chichen Itza and possibly of the nearby city of Ek Balam, and contain a Maya date inscribed which correlates to 869 AD, one of the oldest such dates found in all of Chichen Itza.

In 2009, INAH restored a small ball court that adjoined the back wall of the Casa Colorada.

While the Casa Colorada is in a good state of preservation, other buildings in the group, with one exception, are decrepit mounds. One building is half standing, named Casa del Venado (House of the Deer). The origin of the name is unknown, as there are no representations of deer or other animals on the building.

Central Group

"La Iglesia" in the Las Monjas complex.

The "El Caracol" observatory temple.

Las Monjas is one of the more notable structures at Chichen Itza. It is a complex of Terminal Classic buildings constructed in the Puuc architectural style. The Spanish named this complex Las Monjas ("The Nuns" or "The Nunnery") but it was actually a governmental palace. Just to the east is a small temple (known as the La Iglesia, "The Church") decorated with elaborate masks.

The Las Monjas group is distinguished by its concentration of hieroglyphic texts dating to the Late to Terminal Classic. These texts frequently mention a ruler by the name of Kakupakal.

El Caracol ("The Snail") is located to the north of Las Monjas. It is a round building on a large square platform. It gets its name from the stone spiral staircase inside. The structure, with its unusual placement on the platform and its round shape (the others are rectangular, in keeping with Maya practice), is theorized to have been a proto-observatory with doors and windows aligned to astronomical events, specifically around the path of Venus as it traverses the heavens.

Akab Dzib is located to the east of the Caracol. The name means, in Yucatec Mayan, "Dark Writing"; "dark" in the sense of "mysterious". An earlier name of the building, according to a translation of glyphs in the Casa Colorada, is Wa(k)wak Puh Ak Na, "the flat house with the excessive number of chambers,” and it was the home of the administrator of Chichén Itzá, kokom Yahawal Cho' K’ak’.

INAH completed a restoration of the building in 2007. It is relatively short, only 6 metres (20 ft) high, and is 50 metres (160 ft) in length and 15 metres (49 ft) wide. The long, western-facing façade has seven doorways. The eastern façade has only four doorways, broken by a large staircase that leads to the roof. This apparently was the front of the structure, and looks out over what is today a steep, dry, cenote.

The southern end of the building has one entrance. The door opens into a small chamber and on the opposite wall is another doorway, above which on the lintel are intricately carved glyphs—the “mysterious” or “obscure” writing that gives the building its name today. Under the lintel in the doorjamb is another carved panel of a seated figure surrounded by more glyphs. Inside one of the chambers, near the ceiling, is a painted hand print.

Old Chichen

Composite laser scan image of Chichen Itza's Cave of Balankanche, showing how the shape of its great limestone column is strongly evocative of the World Tree in Maya mythological belief systems. Data from a National Science Foundation/CyArk research partnership.

Old Chichen (or Chichén Viejo in Spanish) is the name given to a group of structures to the south of the central site, where most of the Puuc-style architecture of the city is concentrated.[4] It includes the Initial Series Group, the Phallic Temple, the Platform of the Great Turtle, the Temple of the Owls, and the Temple of the Monkeys.

Other structures

Caves of Balankanche

Approximately 4 km (2.5 mi) south east of the Chichen Itza archaeological zone are a network of sacred caves known as Balankanche (Spanish: Gruta de Balankanche), Balamka'anche' in Yucatec Maya). In the caves, a large selection of ancient pottery and idols may be seen still in the positions where they were left in pre-Columbian times.

The location of the cave has been well known in modern times. Edward Thompson and Alfred Tozzer visited it in 1905. A.S. Pearse and a team of biologists explored the cave in 1932 and 1936. E. Wyllys Andrews IV also explored the cave in the 1930s. Edwin Shook and R.E. Smith explored the cave on behalf of the Carnegie Institution in 1954, and dug several trenches to recover potsherds and other artifacts. Shook determined that the cave had been inhabited over a long period, at least from the Preclassic to the post-conquest era.

On 15 September 1959, José Humberto Gómez, a local guide, discovered a false wall in the cave. Behind it he found an extended network of caves with significant quantities of undisturbed archaeological remains, including pottery and stone-carved censers, stone implements and jewelry. INAH converted the cave into an underground museum, and the objects after being catalogued were returned to their original place so visitors can see them in situ.

Source

Andrews, Anthony P.; E. Wyllys Andrews V; Fernando Robles Castellanos (January 2003). "The Northern Maya Collapse and its Aftermath". Ancient Mesoamerica. New York: Cambridge University Press. 14 (1): 151–156. doi:10.1017/S095653610314103X. ISSN 0956-5361. OCLC 88518111.

Andrews, E. Wyllys, IV (1961). "Excavations at the Gruta De Balankanche, 1959 (Appendix)". Preliminary Report on the 1959–60 Field Season National Geographic Society – Tulane University Dzibilchaltun Program: with grants in aid from National Science Foundation and American Philosophical Society. Middle American Research Institute Miscellaneous Series No 11. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. pp. 28–31. ISBN 0-939238-66-7. OCLC 5628735.

Andrews, E. Wyllys, IV (1970). Balancanche: Throne of the Tiger Priest. Middle American Research Institute Publication No 32. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. ISBN 0-939238-36-5. OCLC 639140.

Anda Alanís; Guillermo de (2007). "Sacrifice and Ritual Body Mutilation in Postclassical Maya Society: Taphonomy of the Human Remains from Chichén Itzá's Cenote Sagrado". In Vera Tiesler; Andrea Cucina. New Perspectives on Human Sacrifice and Ritual Body Treatments in Ancient Maya Society. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. Michael Jochim (series ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 190–208. ISBN 978-0-387-48871-4. ISSN 1568-2722. OCLC 81452956.

Aveni, Anthony F. (1997). Stairways to the Stars: Skywatching in Three Great Ancient Cultures. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-15942-5. OCLC 35559005.

Ball, Philip (14 December 2004). "News: Mystery of 'chirping' pyramid decoded". nature.com. Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/news041213-5. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

Barrera Vásquez, Alfredo (1980). Bastarrachea Manzano, Juan Ramón; Brito Sansores, William, eds. Diccionario maya Cordemex: maya-español, español-maya. with collaborations by Refugio Vermont Salas, David Dzul Góngora, and Domingo Dzul Poot. Mérida, Mexico: Ediciones Cordemex. OCLC 7550928. (Spanish) (Yukatek Maya)

Beyer, Hermann (1937). Studies on the Inscriptions of Chichen Itza (PDF Reprint). Contributions to American Archaeology, No.21. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 3143732. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

Boffil Gómez; Luis A. (30 March 2007). "Yucatán compra 80 has en la zona de Chichén Itzá" [Yucatán buys 80 hectares in the Chichen Itza zone]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City: DEMOS, Desarollo de Medios, S.A. de C.V. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

Boot, Erik (2005). Continuity and Change in Text and Image at Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Mexico: A Study of the Inscriptions, Iconography, and Architecture at a Late Classic to Early Postclassic Maya Site. CNWS Publications no. 135. Leiden, The Netherlands: CNWS Publications. ISBN 90-5789-100-X. OCLC 60520421.

Breglia, Lisa (2006). Monumental Ambivalence: The Politics of Heritage. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71427-4. OCLC 68416845.

Brunhouse, Robert (1971). Sylvanus Morley and the World of the Ancient Mayas. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-0961-9. OCLC 208428.

Cano, Olga (January–February 2002). "Chichén Itzá, Yucatán (Guía de viajeros)". Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). Mexico: Editorial Raíces. IX (53): 80–87. ISSN 0188-8218. OCLC 29789840.

Castañeda, Quetzil E. (1996). In the Museum of Maya Culture: Touring Chichén Itzá. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-2672-3. OCLC 34191010.

Castañeda, Quetzil E. (May 2005). "On the Tourism Wars of Yucatán: Tíich', the Maya Presentation of Heritage" (Reprinted online as "Tourism “Wars” in the Yucatán", AN Commentaries). Anthropology News. Arlington, VA: American Anthropological Association. 46 (5): 8–9. doi:10.1525/an.2005.46.5.8.2. ISSN 1541-6151. OCLC 42453678. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

Chamberlain, Robert S. (1948). The Conquest and Colonization of Yucatán 1517–1550. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 42251506.

Charnay, Désiré (1886). "Reis naar Yucatán". De Aarde en haar Volken, 1886 (in Dutch). Haarlem, Netherlands: Kruseman & Tjeenk Willink. OCLC 12339106. Project Gutenberg etext reproduction [#13346]. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

Charnay, Désiré (1887). Ancient Cities of the New World: Being Voyages and Explorations in Mexico and Central America from 1857–1882. J. Gonino and Helen S. Conant (trans.). New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 2364125.

Cirerol Sansores, Manuel (1948). "Chi Cheen Itsa": Archaeological Paradise of America. Mérida, Mexico: Talleres Graficos del Sudeste. OCLC 18029834.

Clendinnen, Inga (2003). Ambivalent Conquests: Maya and Spaniard in Yucatán, 1517–1570. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37981-4. OCLC 50868309.

Cobos Palma, Rafael (2005) [2004]. "Chichén Itzá: Settlement and Hegemony During the Terminal Classic Period". In Arthur A. Demarest; Prudence M. Rice; Don S. Rice. The Terminal Classic in the Maya Lowlands: Collapse, Transition, and Transformation (paperback ed.). Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 517–544. ISBN 0-87081-822-8. OCLC 61719499.

Coe, Michael D. (1987). The Maya (4th edition, revised ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27455-X. OCLC 15895415.

Coe, Michael D. (1999). The Maya. Ancient peoples and places series (6th edition, fully revised and expanded ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28066-5. OCLC 59432778.

Coggins, Clemency Chase (1984). Cenote of Sacrifice: Maya Treasures from the Sacred Well at Chichen Itza. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-71098-4.

Coggins, Clemency Chase (1992). Artifacts from the Cenote of Sacrifice, Chichén Itzá, Yucatán: Textiles, Basketry, Stone, Bone, Shell, Ceramics, Wood, Copal, Rubber, Other Organic Materials, and Mammalian Remains. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University; distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-87365-694-6. OCLC 26913402.

Colas, Pierre R.; Alexander Voss (2006). "A Game of Life and Death – The Maya Ball Game". In Nikolai Grube (ed.). Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht and Matthias Seidel (assistant eds.). Cologne, Germany: Könemann. pp. 186–191. ISBN 978-3-8331-1957-6. OCLC 71165439.

Cucina, Andrea; Vera Tiesler (2007). "New perspectives on human sacrifice and postsacrifical body treatments in ancient Maya society: Introduction". In Vera Tiesler and Andrea Cucina (eds.). New Perspectives on Human Sacrifice and Ritual Body Treatments in Ancient Maya Society. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. Michael Jochim (series ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-0-387-48871-4. ISSN 1568-2722. OCLC 81452956.

Demarest, Arthur (2004). Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization. Case Studies in Early Societies, No. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59224-0. OCLC 51438896.

Diario de Yucatán (2006-03-03). "Fin a una exención para los mexicanos: Pagarán el día del equinoccio en la zona arqueológica" [End to an exemption for Mexicans: They will have to pay entry to the archaeological zone on the equinox]. Diario de Yucatán (in Spanish). Mérida, Yucatán: Compañía Tipográfica Yucateca, S.A. de C.V. OCLC 29098719.

EFE (29 June 2007). "Chichén Itzá podría duplicar visitantes en 5 años si es declarada maravilla" [Chichen Itza could double visitors in 5 years if declared wonder] (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain. Agencia EFE, S.A.

Freidel, David. "Yaxuna Archaeological Survey: A Report of the 1988 Field Season" (PDF). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

Fry, Steven M. (2009). "The Casa Colorada Ball Court: INAH Turns Mounds into Monuments". www.americanegypt.com. Mystery Lane Press. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

García-Salgado, Tomás (2010). "The Sunlight Effect of the Kukulcán Pyramid or The History of a Line" (PDF). Nexus Network Journal. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán (2007). "Municipios de Yucatán: Tinum" (in Spanish). Mérida, Yucatán: Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

Himpele, Jeffrey D. and Quetzil E. Castañeda (Filmmakers and Producers) (1997). Incidents of Travel in Chichén Itzá: A Visual Ethnography (Documentary (VHS and DVD)). Watertown, MA: Documentary Educational Resources. OCLC 38165182.

Koch, Peter O. (2006). The Aztecs, the Conquistadors, and the Making of Mexican Culture. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. ISBN 0-7864-2252-1. OCLC 61362780.

Kurjack, Edward B.; Ruben Maldonado C.; Merle Greene Robertson (1991). "Ballcourts of the Northern Maya Lowlands". In Vernon Scarborough and David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 145–159. ISBN 0-8165-1360-0. OCLC 51873028.

Landa, Diego de (1937). William Gates (trans.), ed. Yucatan Before and After the Conquest. Baltimore, Maryland: The Maya Society. OCLC 253690044.

Luxton, Richard N. (trans.) (1996). The book of Chumayel : the counsel book of the Yucatec Maya, 1539-1638. Walnut Creek, California: Aegean Park Press. ISBN 0-89412-244-4. OCLC 33849348.

Madeira, Percy (1931). An Aerial Expedition to Central America (Reprint ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. OCLC 13437135.

Masson, Marilyn (2006). "The Dynamics of Maturing Statehood in Postclassic Maya Civilization". In Nikolai Grube. Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht and Matthias Seidel (assistant eds.). Cologne, Germany: Könemann. pp. 340–353. ISBN 978-3-8331-1957-6. OCLC 71165439.

http://chichenitzafacts.com

Miller, Mary Ellen (1999). Maya Art and Architecture. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20327-X. OCLC 41659173.

Morley, Sylvanus Griswold (1913). W. H. R. Rivers; A. E. Jenks; S. G. Morley, eds. Archaeological Research at the Ruins of Chichen Itza, Yucatan. Reports upon the Present Condition and Future Needs of the Science of Anthropology. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 562310877.

Osorio León, José (2006). "La presencia del Clásico Tardío en Chichen Itza (600-800/830 DC)". In J.P. Laporte, B. Arroyo y H. Mejía. XIX Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2005 (PDF) (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología. pp. 455–462. Retrieved 2011-12-15.

Palmquist, Peter E.; Thomas R. Kailbourn (2000). Pioneer Photographers of the Far West: A Biographical Dictionary, 1840–1865. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3883-1. OCLC 44089346.

Pérez de Lara, Jorge (n.d.). "A Tour of Chichen Itza with a Brief History of the Site and its Archaeology". Mesoweb. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

Perry, Richard D. (ed.) (2001). Exploring Yucatan: A Traveler's Anthology. Santa Barbara, CA: Espadaña Press. ISBN 0-9620811-4-0. OCLC 48261466.

Phillips, Charles (2007) [2006]. The Complete Illustrated History of the Aztecs & Maya: The definitive chronicle of the ancient peoples of Central America & Mexico - including the Aztec, Maya, Olmec, Mixtec, Toltec & Zapotec. London: Anness Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-84681-197-X. OCLC 642211652.

http://www.chichenitza.com

Piña Chan, Román (1993) [1980]. Chichén Itzá: La ciudad de los brujos del agua (in Spanish). Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 968-16-0289-7. OCLC 7947748.

Restall, Matthew (1998). Maya Conquistador. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-5506-9. OCLC 38746810.

Roys, Ralph L. (trans.) (1967). The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. OCLC 224990.

Ruiz, Francisco Pérez. "Walled Compounds: An Interpretation of the Defensive System at Chichen Itza, Yucatan" (PDF). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

Schele, Linda; David Freidel (1990). A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya (Reprint ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-688-11204-8. OCLC 145324300.

Schmidt, Peter J. (2007). "Birds, Ceramics, and Cacao: New Excavations at Chichén Itzá, Yucatan". In Jeff Karl Kowalski; Cynthia Kristan-Graham. Twin Tollans: Chichén Itzá, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection : Distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-88402-323-0. OCLC 71243931.

SECTUR (2006). Compendio Estadístico del Turismo en México 2006. Mexico City: Secretaría de Turismo (SECTUR).

SECTUR (7 July 2007). "Boletín 069: Declaran a Chichén Itzá Nueva Maravilla del Mundo Moderno" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Secretaría de Turismo. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

Sharer, Robert J.; Loa P. Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446.

http://www.nationalgeographic.com

Thompson, J. Eric S. (1966) [1954]. The Rise and Fall of Maya Civilization. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0301-9. OCLC 6611739.

https://en.wikipedia.org

Tozzer, Alfred Marston; Glover Morrill Allen (1910). Animal figures in the Maya codices. 4 (Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Museum. OCLC 2199473.

Usborne, David (7 November 2007). "Mexican standoff: the battle of Chichen Itza". The Independent. Independent News & Media. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

Voss, Alexander W.; H. Juergen Kremer (2000). Pierre Robert Colas (ed.), ed. K'ak'-u-pakal, Hun-pik-tok' and the Kokom: The Political Organization of Chichén Itzá (PDF). Markt Schwaben, Germany: Verlag Anton Saurwein. ISBN 3-931419-04-5 OCLC 47871840.

Weeks, John M.; Jane A. Hill (2006). The Carnegie Maya: the Carnegie Institution of Washington Maya Research Program, 1913–1957. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0-87081-833-2. OCLC 470645719.

Willard, T.A. (1941). Kukulcan, the Bearded Conqueror : New Mayan Discoveries. Hollywood, California: Murray and Gee. OCLC 3491500.

Andrews, E. Wyllys, IV (1961). "Excavations at the Gruta De Balankanche, 1959 (Appendix)". Preliminary Report on the 1959–60 Field Season National Geographic Society – Tulane University Dzibilchaltun Program: with grants in aid from National Science Foundation and American Philosophical Society. Middle American Research Institute Miscellaneous Series No 11. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. pp. 28–31. ISBN 0-939238-66-7. OCLC 5628735.

Andrews, E. Wyllys, IV (1970). Balancanche: Throne of the Tiger Priest. Middle American Research Institute Publication No 32. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. ISBN 0-939238-36-5. OCLC 639140.

Anda Alanís; Guillermo de (2007). "Sacrifice and Ritual Body Mutilation in Postclassical Maya Society: Taphonomy of the Human Remains from Chichén Itzá's Cenote Sagrado". In Vera Tiesler; Andrea Cucina. New Perspectives on Human Sacrifice and Ritual Body Treatments in Ancient Maya Society. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. Michael Jochim (series ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 190–208. ISBN 978-0-387-48871-4. ISSN 1568-2722. OCLC 81452956.

Aveni, Anthony F. (1997). Stairways to the Stars: Skywatching in Three Great Ancient Cultures. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-15942-5. OCLC 35559005.

Ball, Philip (14 December 2004). "News: Mystery of 'chirping' pyramid decoded". nature.com. Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/news041213-5. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

Barrera Vásquez, Alfredo (1980). Bastarrachea Manzano, Juan Ramón; Brito Sansores, William, eds. Diccionario maya Cordemex: maya-español, español-maya. with collaborations by Refugio Vermont Salas, David Dzul Góngora, and Domingo Dzul Poot. Mérida, Mexico: Ediciones Cordemex. OCLC 7550928. (Spanish) (Yukatek Maya)

Beyer, Hermann (1937). Studies on the Inscriptions of Chichen Itza (PDF Reprint). Contributions to American Archaeology, No.21. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 3143732. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

Boffil Gómez; Luis A. (30 March 2007). "Yucatán compra 80 has en la zona de Chichén Itzá" [Yucatán buys 80 hectares in the Chichen Itza zone]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City: DEMOS, Desarollo de Medios, S.A. de C.V. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

Boot, Erik (2005). Continuity and Change in Text and Image at Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Mexico: A Study of the Inscriptions, Iconography, and Architecture at a Late Classic to Early Postclassic Maya Site. CNWS Publications no. 135. Leiden, The Netherlands: CNWS Publications. ISBN 90-5789-100-X. OCLC 60520421.

Breglia, Lisa (2006). Monumental Ambivalence: The Politics of Heritage. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71427-4. OCLC 68416845.

Brunhouse, Robert (1971). Sylvanus Morley and the World of the Ancient Mayas. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-0961-9. OCLC 208428.

Cano, Olga (January–February 2002). "Chichén Itzá, Yucatán (Guía de viajeros)". Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). Mexico: Editorial Raíces. IX (53): 80–87. ISSN 0188-8218. OCLC 29789840.

Castañeda, Quetzil E. (1996). In the Museum of Maya Culture: Touring Chichén Itzá. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-2672-3. OCLC 34191010.

Castañeda, Quetzil E. (May 2005). "On the Tourism Wars of Yucatán: Tíich', the Maya Presentation of Heritage" (Reprinted online as "Tourism “Wars” in the Yucatán", AN Commentaries). Anthropology News. Arlington, VA: American Anthropological Association. 46 (5): 8–9. doi:10.1525/an.2005.46.5.8.2. ISSN 1541-6151. OCLC 42453678. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

Chamberlain, Robert S. (1948). The Conquest and Colonization of Yucatán 1517–1550. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 42251506.

Charnay, Désiré (1886). "Reis naar Yucatán". De Aarde en haar Volken, 1886 (in Dutch). Haarlem, Netherlands: Kruseman & Tjeenk Willink. OCLC 12339106. Project Gutenberg etext reproduction [#13346]. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

Charnay, Désiré (1887). Ancient Cities of the New World: Being Voyages and Explorations in Mexico and Central America from 1857–1882. J. Gonino and Helen S. Conant (trans.). New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 2364125.

Cirerol Sansores, Manuel (1948). "Chi Cheen Itsa": Archaeological Paradise of America. Mérida, Mexico: Talleres Graficos del Sudeste. OCLC 18029834.

Clendinnen, Inga (2003). Ambivalent Conquests: Maya and Spaniard in Yucatán, 1517–1570. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37981-4. OCLC 50868309.

Cobos Palma, Rafael (2005) [2004]. "Chichén Itzá: Settlement and Hegemony During the Terminal Classic Period". In Arthur A. Demarest; Prudence M. Rice; Don S. Rice. The Terminal Classic in the Maya Lowlands: Collapse, Transition, and Transformation (paperback ed.). Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. pp. 517–544. ISBN 0-87081-822-8. OCLC 61719499.

Coe, Michael D. (1987). The Maya (4th edition, revised ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27455-X. OCLC 15895415.

Coe, Michael D. (1999). The Maya. Ancient peoples and places series (6th edition, fully revised and expanded ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28066-5. OCLC 59432778.

Coggins, Clemency Chase (1984). Cenote of Sacrifice: Maya Treasures from the Sacred Well at Chichen Itza. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-71098-4.

Coggins, Clemency Chase (1992). Artifacts from the Cenote of Sacrifice, Chichén Itzá, Yucatán: Textiles, Basketry, Stone, Bone, Shell, Ceramics, Wood, Copal, Rubber, Other Organic Materials, and Mammalian Remains. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University; distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-87365-694-6. OCLC 26913402.

Colas, Pierre R.; Alexander Voss (2006). "A Game of Life and Death – The Maya Ball Game". In Nikolai Grube (ed.). Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht and Matthias Seidel (assistant eds.). Cologne, Germany: Könemann. pp. 186–191. ISBN 978-3-8331-1957-6. OCLC 71165439.

Cucina, Andrea; Vera Tiesler (2007). "New perspectives on human sacrifice and postsacrifical body treatments in ancient Maya society: Introduction". In Vera Tiesler and Andrea Cucina (eds.). New Perspectives on Human Sacrifice and Ritual Body Treatments in Ancient Maya Society. Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology. Michael Jochim (series ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-0-387-48871-4. ISSN 1568-2722. OCLC 81452956.

Demarest, Arthur (2004). Ancient Maya: The Rise and Fall of a Rainforest Civilization. Case Studies in Early Societies, No. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59224-0. OCLC 51438896.

Diario de Yucatán (2006-03-03). "Fin a una exención para los mexicanos: Pagarán el día del equinoccio en la zona arqueológica" [End to an exemption for Mexicans: They will have to pay entry to the archaeological zone on the equinox]. Diario de Yucatán (in Spanish). Mérida, Yucatán: Compañía Tipográfica Yucateca, S.A. de C.V. OCLC 29098719.

EFE (29 June 2007). "Chichén Itzá podría duplicar visitantes en 5 años si es declarada maravilla" [Chichen Itza could double visitors in 5 years if declared wonder] (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain. Agencia EFE, S.A.

Freidel, David. "Yaxuna Archaeological Survey: A Report of the 1988 Field Season" (PDF). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

Fry, Steven M. (2009). "The Casa Colorada Ball Court: INAH Turns Mounds into Monuments". www.americanegypt.com. Mystery Lane Press. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

García-Salgado, Tomás (2010). "The Sunlight Effect of the Kukulcán Pyramid or The History of a Line" (PDF). Nexus Network Journal. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán (2007). "Municipios de Yucatán: Tinum" (in Spanish). Mérida, Yucatán: Gobierno del Estado de Yucatán. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

Himpele, Jeffrey D. and Quetzil E. Castañeda (Filmmakers and Producers) (1997). Incidents of Travel in Chichén Itzá: A Visual Ethnography (Documentary (VHS and DVD)). Watertown, MA: Documentary Educational Resources. OCLC 38165182.

Koch, Peter O. (2006). The Aztecs, the Conquistadors, and the Making of Mexican Culture. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. ISBN 0-7864-2252-1. OCLC 61362780.

Kurjack, Edward B.; Ruben Maldonado C.; Merle Greene Robertson (1991). "Ballcourts of the Northern Maya Lowlands". In Vernon Scarborough and David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 145–159. ISBN 0-8165-1360-0. OCLC 51873028.

Landa, Diego de (1937). William Gates (trans.), ed. Yucatan Before and After the Conquest. Baltimore, Maryland: The Maya Society. OCLC 253690044.

Luxton, Richard N. (trans.) (1996). The book of Chumayel : the counsel book of the Yucatec Maya, 1539-1638. Walnut Creek, California: Aegean Park Press. ISBN 0-89412-244-4. OCLC 33849348.

Madeira, Percy (1931). An Aerial Expedition to Central America (Reprint ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. OCLC 13437135.

Masson, Marilyn (2006). "The Dynamics of Maturing Statehood in Postclassic Maya Civilization". In Nikolai Grube. Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Eva Eggebrecht and Matthias Seidel (assistant eds.). Cologne, Germany: Könemann. pp. 340–353. ISBN 978-3-8331-1957-6. OCLC 71165439.

http://chichenitzafacts.com

Miller, Mary Ellen (1999). Maya Art and Architecture. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20327-X. OCLC 41659173.

Morley, Sylvanus Griswold (1913). W. H. R. Rivers; A. E. Jenks; S. G. Morley, eds. Archaeological Research at the Ruins of Chichen Itza, Yucatan. Reports upon the Present Condition and Future Needs of the Science of Anthropology. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. OCLC 562310877.

Osorio León, José (2006). "La presencia del Clásico Tardío en Chichen Itza (600-800/830 DC)". In J.P. Laporte, B. Arroyo y H. Mejía. XIX Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2005 (PDF) (in Spanish). Guatemala City, Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología. pp. 455–462. Retrieved 2011-12-15.

Palmquist, Peter E.; Thomas R. Kailbourn (2000). Pioneer Photographers of the Far West: A Biographical Dictionary, 1840–1865. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3883-1. OCLC 44089346.

Pérez de Lara, Jorge (n.d.). "A Tour of Chichen Itza with a Brief History of the Site and its Archaeology". Mesoweb. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

Perry, Richard D. (ed.) (2001). Exploring Yucatan: A Traveler's Anthology. Santa Barbara, CA: Espadaña Press. ISBN 0-9620811-4-0. OCLC 48261466.

Phillips, Charles (2007) [2006]. The Complete Illustrated History of the Aztecs & Maya: The definitive chronicle of the ancient peoples of Central America & Mexico - including the Aztec, Maya, Olmec, Mixtec, Toltec & Zapotec. London: Anness Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-84681-197-X. OCLC 642211652.

http://www.chichenitza.com

Piña Chan, Román (1993) [1980]. Chichén Itzá: La ciudad de los brujos del agua (in Spanish). Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 968-16-0289-7. OCLC 7947748.

Restall, Matthew (1998). Maya Conquistador. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-5506-9. OCLC 38746810.

Roys, Ralph L. (trans.) (1967). The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. OCLC 224990.

Ruiz, Francisco Pérez. "Walled Compounds: An Interpretation of the Defensive System at Chichen Itza, Yucatan" (PDF). Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

Schele, Linda; David Freidel (1990). A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya (Reprint ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-688-11204-8. OCLC 145324300.

Schmidt, Peter J. (2007). "Birds, Ceramics, and Cacao: New Excavations at Chichén Itzá, Yucatan". In Jeff Karl Kowalski; Cynthia Kristan-Graham. Twin Tollans: Chichén Itzá, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection : Distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-88402-323-0. OCLC 71243931.

SECTUR (2006). Compendio Estadístico del Turismo en México 2006. Mexico City: Secretaría de Turismo (SECTUR).

SECTUR (7 July 2007). "Boletín 069: Declaran a Chichén Itzá Nueva Maravilla del Mundo Moderno" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Secretaría de Turismo. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

Sharer, Robert J.; Loa P. Traxler (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th (fully revised) ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4817-9. OCLC 57577446.

http://www.nationalgeographic.com

Thompson, J. Eric S. (1966) [1954]. The Rise and Fall of Maya Civilization. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0301-9. OCLC 6611739.

https://en.wikipedia.org

Tozzer, Alfred Marston; Glover Morrill Allen (1910). Animal figures in the Maya codices. 4 (Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Museum. OCLC 2199473.

Usborne, David (7 November 2007). "Mexican standoff: the battle of Chichen Itza". The Independent. Independent News & Media. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

Voss, Alexander W.; H. Juergen Kremer (2000). Pierre Robert Colas (ed.), ed. K'ak'-u-pakal, Hun-pik-tok' and the Kokom: The Political Organization of Chichén Itzá (PDF). Markt Schwaben, Germany: Verlag Anton Saurwein. ISBN 3-931419-04-5 OCLC 47871840.

Weeks, John M.; Jane A. Hill (2006). The Carnegie Maya: the Carnegie Institution of Washington Maya Research Program, 1913–1957. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0-87081-833-2. OCLC 470645719.

Willard, T.A. (1941). Kukulcan, the Bearded Conqueror : New Mayan Discoveries. Hollywood, California: Murray and Gee. OCLC 3491500.

Israel Leal, AP

No comments:

Write σχόλια